Summer Means Orchid Hunting

As the annual Hexalectris survey at Cedar Ridge (Texas) is preparing to commence on Tuesday, June 5, we are once again reminded of the amazing biodiversity of Texas flora.

Hexalectris spicata

photo by Alan Cressler

Stephanie Varnum of the Dallas Chapter of the Texas Master Naturalists will again lead the survey, and everyone interested in participating is welcome to join us. The surveys begin early, in order to take advantage of the coolest part of the day.

Every Tuesday and Thursday, beginning June 5, and continuing for six weeks, we will meet at the park benches of the Cedar Ridge Preserve for the 8 AM briefing. Occasionally the starting point will be at a different part of the park, so be sure to add your name to the email list to get updates. (OrchidArtbyCharlesHess@yahoo.com)

How to prepare for one of these outings? Dress in cool, light-colored clothes, bring water, wear sturdy shoes, and bring insect repellent. The walk along the survey trail takes 2-3 hours; you will be on your way home before noon.

- On the way we can expect to see several species of Hexalectris, such as nitida, warnockii, and spicata. These small orchids remind us every year of the natural beauty to be found in Texas. It is always a very special treat to see them in their natural habitat only 30 miles from Dallas.

platanthera chapmanii in situ close-up

For Texas orchid lovers who are willing and able to take a longer drive, there is another Texas treasure where native orchids can be found. The Watson Rare Native Plant Preserve near Lake Hyatt Lake in the Big Thicket National Preserve is the site in question. (For directions, see http://www.watsonpreserve.org/p/directions.html)

In the month of August the rare Platanthera chapmanii (Chapman’s Fringed Orchid) can be found growing in wet areas, along with other bog plants, as well as four types of carnivorous plants native to the Southern Coastal Plain region. Joe Liggio, author of Wild Orchids of Texas will be conducting the tours. (If interested, contact me for further information at OrchidArtbyCharlesHess@yahoo.com)

Hexalectris arizonica

The orchids of this region have been preserved through the remarkable foresight of Geraldine Watson, a pioneer in conservation of Texas’ native species. Watson was born in Louisiana in 1925 but later moved to the Piney Woods of East Texas, where she learned to appreciate the complex ecosystem of this historic area. After earning her degree in biology, she began working for the National Parks Service. During her 15-year tenure there she came upon a plot of land so biologically rich that she felt moved to begin purchasing plots little by little, until she was able to establish a 10 acre preserve, which she named the Watson Pineland Preserve.

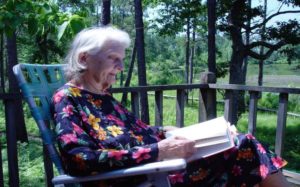

Geraldine Watson 1925-2012

Watson saw the value of the Big Thicket’s biodiversity, and began a campaign to establish the Big Thicket National Preserve. It was an uphill battle. Despite being readily accepted by garden clubs, where she gave hundreds of presentations, and even being permitted to testify before Congress, she was hated by the lumber companies, who were systematically devastating the old growth forests that early settlers called the Big Thicket. At one time pine forests covered the South from Texas to Florida, with trees up to 6 feet in diameter. Of course such natural riches were of great interest to the lumber companies, and they constantly undermined Watson’s efforts at preservation.

She persisted, however, and her tenacity paid off in 1974, when President Gerald Ford signed legislation establishing the preserve which is now more than 105,000 acres, and meanders throughout several Texas counties.

From an orchid conservation standpoint, the Watson Rare Native Plant Preserve is the focus of very important research. Pauline Singleton’s blog post in November 2018 covers this ongoing effort:

Dr. Jyotsna Sharma, who is an Associate Professor at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, TX, is leading conservation research projects at Watson Native Plant Preserve since 2012. The focus of her lab’s work is on one of the rare and superbly showy orchids of Texas. Platanthera chapmanii (Chapman’s orchid) is known from only a few locations in southeastern Texas, and Watson Native Plant Preserve hosts the largest population in Texas. Her work has included:

1) augmenting the native population of the species

2) locating new populations of the species in Big Thicket National Preserve

3) developing effective propagation methods for P. chapmanii, and

4) study of mycorrhizal ecology of the species. In nature, all orchid seeds depend on mycorrhizal fungi for germination, and as seedlings develop into mature plants, they maintain this relationship with their partner fungi.

Graduate (M.S.) student Kirsten E. Poff conducted manipulative experiments to test questions related to propagation and mycorrhizal symbiosis. Ms. Poff graduated in 2016 and is now a Ph.D. student at the University of Hawaii

Other team members: Mr. Joe Liggio, Mr. Jim Willis, and Ms. Pauline Singleton assisted with research activities and facilitated permits and other logistics. Without their help, none of the activities would have been possible.

Two-year old laboratory-cultured plants of Platanthera chapmanii were planted at Watson Native Plant Preserve. Survival and emergence has been recorded at >90% two years after planting. Over the years, Dr. Sharma’s team has added hundreds of plants of the species to WNPP

Publications:

Richards M and J Sharma. 2014. A review of conservation efforts for Platanthera chapmanii in Texas and Georgia. Native Orchid Conference Journal 11: 1-11. ISSN 1554-1169.

Poff, KE. 2016. Platanthera chapmanii: culture, population augmentation, and mycorrhizal associations. M.S. thesis (Supervisor: J. Sharma). Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX. pp. 142.

Poff, KE, J Sharma, and M Richards. 2016. Cold-moist stratification improves germination in a temperate terrestrial orchid. Castanea 81: xx-xx. (In Press)

So, if you are looking for an orchid adventure and a chance to see native Texas orchids in their natural habitats, you now have two opportunities to do exactly that.

Happy orchid hunting for all this summer.![]()