Where have all the pollinators gone?

Every July in Texas the Hexalectris survey at Cedar Ridge is in full swing. The Citizen Scientist survey (led by Stephanie Varnum, North Texas Master Naturalists) is a rare opportunity for local orchid lovers to participate in orchid conservation efforts. Developing a love and respect for nature’s wonders is the bedrock of conservation. We protect and preserve what we love and understand, so it is vital to develop an awareness of the world in which these unique plants thrive.

Here in Texas we are fortunate to have several local species, such as the nidita, spicata, and arizonica. During this, the third week of the survey, the Hexalectris warnockii, perhaps the most beautiful of Texas orchid species, is taking center stage. Our team of 7 who participated in the survey on Jun 19 tagged over 75 individual spikes, ranging from 1 cm to 25 cm tall. Just one short week ago, we tagged only 40, so we can see they are starting the most visibly active part of their life cycle, rapidly emerging from the limestone-rich soil which is their habitat.

The sight of an open Hexalectris warnockii flower is enough to remind us of why this species is the symbol of our South West Regional Orchid Growers Association, centered in Texas. This species was named after Dr. Barton Warnock, who collected it in 1937 in what in now called the Big Bend National Park in West Texas. We are fortunate to have this beautiful orchid here in Dallas County, as there are only 8 other counties (according to Joe Liggio’s Wild orchid of Texas) where the Hexalectris warnockii is found. Needless to say, it is considered rare. The limestone soils and the cedars of Cedar Ridge combine to make an ideal habitat for this little gem of a plant.

The sight of an open Hexalectris warnockii flower is enough to remind us of why this species is the symbol of our South West Regional Orchid Growers Association, centered in Texas. This species was named after Dr. Barton Warnock, who collected it in 1937 in what in now called the Big Bend National Park in West Texas. We are fortunate to have this beautiful orchid here in Dallas County, as there are only 8 other counties (according to Joe Liggio’s Wild orchid of Texas) where the Hexalectris warnockii is found. Needless to say, it is considered rare. The limestone soils and the cedars of Cedar Ridge combine to make an ideal habitat for this little gem of a plant.

This year (2018) the mission of the Citizen Scientist Survey has an additional emphasis, which is to look for pollinators, particularly now as the blooms start to open. Only one of the spikes tagged today had open flowers, meaning that they are just now starting to show their beauty and appeal to pollinators.

Finding and observing the pollinator of this species is no easy task. Recent history from Stephanie Varnum’s documentation shows pollination having occurred on only 2% – 3% of the emerged spikes. One would expect that as the flowers open, the pollinators would appear, but to my knowledge, the identity of the actual pollinator is not known. Patience is the name of the game here. In time a survey participant will catch a pollinator in the act, and with luck, will have a camera at the ready. Then we will have more complete knowledge of this orchid’s life cycle.

In the orchid world, a classic example of patience was finding the pollinator for the “Darwin orchid”, or Angraecum sesquipedale. It was unknown for decades how this orchid was pollinated. But finally, with the development of low light photography, a dedicated scientist was able to capture the Xanthopan morganii praedicta moth feeding at night, using its 12-inch proboscis to reach the nectar in the equally long nectary of this Madagascar orchid.

The plight of pollinators is much in the news these days with the recently alarming reports from Germany that the insect population count is down 40%. (https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/insect-ldquo-armageddon-rdquo-5-crucial-questions-answered/) This is an alarming development. Insects are an essential part of a healthy ecosystem. As an analogy, imagine what would happen if 40% of the gears in your grandfather clock disappeared. Would you expect that clock to function? Nature works the same way; all the parts must be in place, for life to go on. If the insects perish, birds will lose their food supply. And on it goes. A frightening prospect, to say the least.

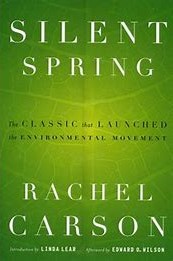

Along with the example of the grandfather clock, we have a 50-year old classic book, still entirely relevant today. It is Rachel Carson’s 1962 classic Silent Spring, which first introduced the world to the interconnectedness of all the “gears” of nature. Carson first alerted us to the danger of the rapid development and use of new lethal biocides. These products, which initially promised to be the panacea for all agricultural pest control, far outstretched the chemical industry’s research on their detrimental effects on our ecosystem. It was through Carson’s research and writing that the world became aware of the destructive impact of DDT on our planet’s ecosystem. As a result, DDT was eventually banned in most countries.

Along with the example of the grandfather clock, we have a 50-year old classic book, still entirely relevant today. It is Rachel Carson’s 1962 classic Silent Spring, which first introduced the world to the interconnectedness of all the “gears” of nature. Carson first alerted us to the danger of the rapid development and use of new lethal biocides. These products, which initially promised to be the panacea for all agricultural pest control, far outstretched the chemical industry’s research on their detrimental effects on our ecosystem. It was through Carson’s research and writing that the world became aware of the destructive impact of DDT on our planet’s ecosystem. As a result, DDT was eventually banned in most countries.

Unfortunately, just like the grandfather clocks, Carson’s warning chimes for the destruction of our environment have been silenced to the point of being forgotten. The Rachael Carsons of today are still risking life and career to sound environmental alarms, particularly on matters critical to protecting our food crop pollinators. A recent interview with Andrew Kimbrell, Executive Director of the Center for Food Safety, explains the dangers to our food supply, particularly the endangerment of pollinators, and the prevalence of genetically modified crops, which make up a huge proportion of our agricultural products.

Kimbrell explains how former food crops have been turned into commodities by the agricultural industry. These crops, grown for feeding cattle, hogs and chickens, are routinely sprayed with vast amounts of pesticides and herbicides. In the process of applying these poisonous substances, many important elements of the food chain also perish, including the plants which attract and feed the pollinators. It is not an over-simplification to say that without the work of pollinators, humans cannot survive![]()