Margaritas and Mayan Orchids

When we think of tropical forest, the Amazon is what immediately comes to mind as an area resplendent with biodiversity, a complex ecosystem, and, of course, many orchid species. But there is another area, much closer, which is also very important to orchid conservation, and it is very near to a popular vacation resort in Mexico.

For many snorkeling fans or beach lovers, Cancún was or still is a favorite destination for a summer or winter getaway. But that was not the reason for our most recent visit. We went mainly to see local orchids. Okay, truth be told, maybe just one little margarita or two after a long day, trekking around the forest, looking for orchids.

Selva Maya tropical forest region, Mexico

Even though we did not know this while there, we were actually at the northern end of the second largest tropical forest in the Americas (the Amazon being the largest). This forest, which begins near Cancún, consists of a breath-taking 25 million acres in Mexico alone, covering the entire Yucatán peninsula.

The remaining portion of the forest extends into two Central American countries, Guatemala and Belize. All told, it comprises a 38-million-acre forest called Selva Maya. Most of us know that this area contains archeological remains of the vast Mayan empire. But the area has recently become known for an equally important treasure, that being the vast forest itself, now the subject of numerous preservation efforts.

Not only does this forest contain enormous biodiversity, much of it still unexplored and uncatalogued, but it is also an enormous carbon sink. Nature has everything figured out so beautifully. We exhale Carbon Dioxide (one part Carbon, two parts Oxygen), the plants take it up, use the carbon for their photosynthesis process, and release the oxygen back into the atmosphere.

Removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is important for combatting climate change, while releasing oxygen is vital to all organisms, including humans, which depend on oxygen for our survival. The challenge here is to keep these rainforests intact as much as we can, or at least as long as we wish to continue breathing. For a little refresher about how plants perform their magic, click here.

For us orchid lovers these forests have an additional attraction, because they are home for 117 orchid species. The March 2011 issue of AOS Orchids contains beautiful descriptions and photos of orchids found in the Yucatán peninsula in an article entitled “Orchids amid the Ruins” by Susan Ludmer-Gliebe, a freelance writer and photographer. (If your stash of AOS magazines does not extend that far back, never fear – the article is also available at the AOS website).

Brassavola venusa AOS photo by Leon Ibarra Gonzalez

Ludmer-Gliebe paints a wonderful picture of the local terrain much, of which had remained unexplored until the 1930’s when the ancient Mayan ruins were first discovered. Due to the uniformity of the terrain

this area does not contain the most prolific biodiversity of orchid species in Mexico, and represents only about 10% of what Mexico offers. Its highest peak on this limestone shelf is only 800 feet. By comparison, Nicaragua, which is so small that its area is only about the size of the Yucatán, has four times the number of orchid species.

The 1.5 million-acre Calakmul Biosphere enjoys world-wide recognition, having been declared “one of the most important tropical forest regions of North America with 1,500 species of plants, including 73 orchid species”.

The Nature Conservancy has been working in the Yucatán Peninsula for 30 years helping protect this and other Biosphere Reserves around the famous archeological ruins. Recently their efforts have extended to also helping protect forests outside of these preserves. Deforestation outside of the preserves is around 200,000 acres per year, half of this loss being a result of clearing by cattle ranchers, and about a third from cutting and burning to open new fields for agriculture.

Prosthechea radiata AOS photo by Leon Ibarra Gonzalez

The Nature Conservancy’s Fall 2017 magazine issue features articles about projects designed to slow down tropical deforestation which, worldwide, contributes 15% of annual greenhouse emissions. What makes these projects look so promising is that they replicate nature while at the same time building on and helping to maintain 4000 year old Mayan agricultural methods. As a result they are able to practice “sustainable intensification”, a process which improves both agriculture and cattle ranching.

Why are rain forests lost at such alarming rates? It is because in rainforests the layer of fertile soil is surprisingly thin. After clearcutting and converting to agriculture or cattle ranching, the land remains fertile for only a few years, after which time the land is abandoned and a new area of rain forest is cut down, repeating this wasteful and unsound practice.

By contrast, modern “conservation tilling” allows the soil to preserve its nutrients, thereby improving crop yield and reducing the need for clearing additional land. Farmers do this by tilling their fields only once every four years. They plow deeply to break up the soil, but in the other three years they harvest their crops and leave the stubble in the field, creating a mulch which returns nutrients back into the soil.

This process is further enhanced by adding the ancient Mayan practice of growing up to 15 different plants together in one field, thereby reducing the need to add additional fertilizer. The clever Mayans figured out that plants growing together in the same area are able to complement each other in amazing ways. For example, beans replenish the soil with nitrogen, which is a valuable nutrient for the other plants. Even with all our modern knowledge, we have much to learn from ancient civilizations which were very much in tune with the nature.

Land used for raising cattle can also be treated more efficiently. Ranchers are learning that by replicating the movements of herds as found in nature, along with planting shade trees in currently un-used areas, the number of cattle sustained can be increased by a factor of three.

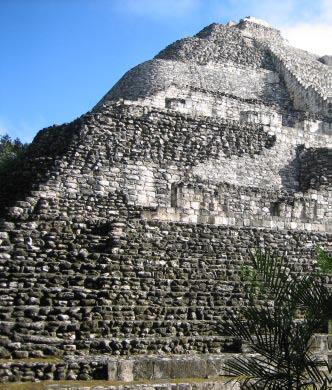

The Great pyramid at Calakmul Photo by Leon Ibarra Gonzalez

These methodologies have been modeled in experiments on the Yucatán peninsula. Governors of the three Yucatán states have committed to a goal of net-zero deforestation by 2030. They will do this by combining the agricultural methods above with a systematic plan for reforestation. Net-zero deforestation with its vague and flexible definition has been known to allow deforestation if it is accompanied by replanting. This will cause Mexico to be one of three countries that will be able to sell carbon offsets. We can then expect that the more powerful agricultural interests will be moving into the area. Think cattle.

Only time will tell whether these efforts will be a complete success. Climate change has already altered the reliability of wet and dry seasons on the peninsula. In addition, we now know from history that the droughts in the ninth century likely played a major part in the loss of the Mayan civilization, despite their advanced water management systems. Ludmer-Gliebe tells us that at the Calakmul reserve, for example, “archaeologists have discovered that the inhabitants of that huge Mayan city, responding to the need for a continual source of drinking water during the winter dry season, had built the most sophisticated and largest water management systems in the Mayan world, including 17 public reservoirs, one of which is used to this day”.

This delicate ecosystem of the Americas will be an interesting experiment as we adapt to the new climate norms. Stay tuned.

![]()