Opportunities Abound for local orchid conservation. Who Knew?

Little pencil-like stalks are just starting to emerge from the leaf litter under certain cedar trees. Yes, that’s right, we have orchids growing in the parks around Dallas. This is the time of year when the local terrestrial orchids make their annual appearance.

The Master Naturalists Citizen Scientist Orchid Project meets mornings twice a week at Cedar Ridge Preserve south of Dallas beginning in early June and continuing through the end of July. Participants will tag each sighting along two different trails. The count is taken each year and has been tabulated for more than 10 years already. Anyone who loves orchids is encouraged to take advantage of this program by joining the Master Naturalists on one of these outings.

Hexalectris nitida orchid

A typical survey takes about three hours, with up to 10 people taking part. Orchids most commonly found are the Hexalectris varieties of nitida, arizonica, and our own symbol of our society, the Hexalectris warnockii. Also, sighted in the past have been the Hexalectris spicata, which is the model chosen by our own society and SWROGA to sponsor for the Smithsonian’s educational Orchid-Gami project.

For many in the naturalist group, and for most of us orchid society enthusiasts, this is the only time of year to go orchid hunting. This experience is very different from the orchid hunting we are most familiar with, where the plants are labeled

Hexalectris arizonica orchid

and have price tags on them. Here, the only tags are the ones we place, and the plants do not go home with us. These plants are best viewed and enjoyed in the wild. These orchids are able to thrive only in the fungi-filled habitat associated with the roots of the cedar trees. This habitat is virtually impossible to re-create in a home or greenhouse. If that fact is not enough to discourage someone from digging up one of these orchids, there is the added factor that it is highly illegal to remove one of them from their location in the wild. See photos of our recent survey outing here.

If you are interested in volunteering for orchid preservation and research, but tromping around in the woods is not exactly your cup of tea, there is another possibility.

Hexalectris spicata orchid

photo by Alan Cressler

The Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) in Fort Worth is doing some fascinating and valuable work on orchid preservation. Their building is located on the grounds of the Fort Worth Botanical Gardens, and is a modern facility with temperature and humidity controlled storage of herbarium records of plants from all over the world. I have been training as a volunteer, learning skills that range from mounting plant specimens, applying stick-on bar codes, to database entry. The work is not difficult, and they have an excellent staff to train and supervise volunteer activity. As an added bonus, the BRIT is accessible via public transportation. A single DART day-pass will take you all the way to the Brit, and then home again when your volunteer work is finished for the day. All you have to do is take a DART train or bus to Union Station in Dallas, ride the Trinity River Express (TRE) to Fort Worth, and then catch the #7 bus, which takes you to the BRIT. What could be easier? And think of all the good reading you can enjoy on the way, without worrying about traffic.

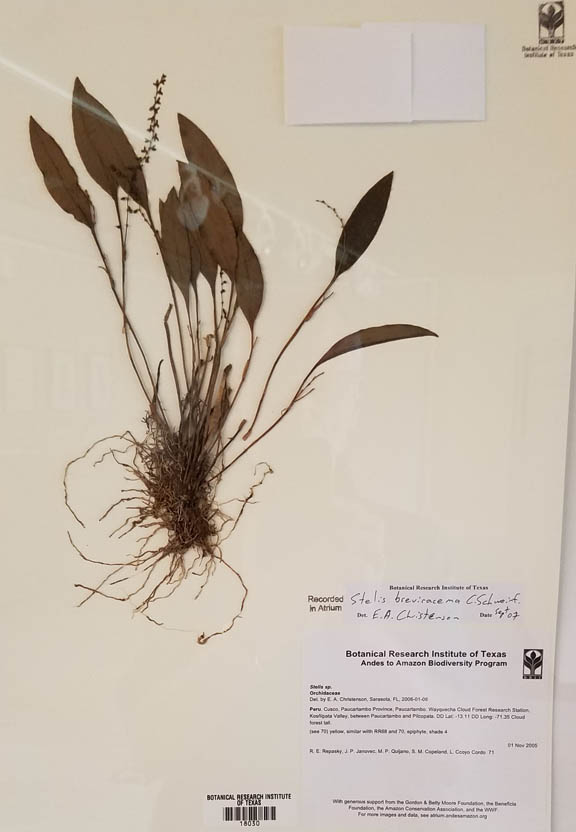

Herbarium sample

I love to learn new things, and I like the feeling of contributing as a volunteer, as time permits. For these reasons, volunteering at the BRIT is an ideal match. Not only does the BRIT benefit from the hours I volunteer working on botanic specimen conservation, the BRIT also gets a matching monetary donation for these volunteer hours from Texas Instruments, where I was employed during my entire career.

I am especially excited at the prospects of working with the BRIT’s treasure trove of Philippines orchid herbarium records. During a tour of the facility, a senior botanist revealed that they have acquired a collection which they are planning to put on-line with an indexed database. Such a project requires either substantial funding, or the efforts of some willing volunteers. Only then will these botanical specimen sheets be readily available to researchers. Currently these records can be seen only by researchers who are able to visit the BRIT in person. Such valuable information should be available to the outside world, where researchers from anywhere can access it via the Internet.

One of the recently completed projects is the online database of the Andes to Amazon Biodiversity Program (AABP). Attached is an example of a Stelis breviracema collected in 2005 and annotated by the late Eric Christenson, the well-known orchid taxonomist. This program contains more than 10,000 herbarium specimens of Ecuadorian flora and can be viewed at atrium.andesamazon.org. The samples were collected during an inventory taken between 2004 to 2012 in an area ranging from the high Andes to the Amazonian lowlands. In this modern age of research, digital photos of the flowers are included along with the traditional specimen sheet documentation.

Whether or not you delve deep into the wooded forests of Cedar Ridge Preserve, or become lost in the archives at the BRIT, perhaps the most important take-away is that we expand our appreciation of the botanic treasures all around us, and realize how diverse and complex the world truly is. We all share the responsibility to protect and preserve this ecosystem, not only for the beauty of orchids we grow and show, but for the survival of the entire Earth’s eco-system, which includes the human race.![]()