Happiness – and orchid conservation – could be the same thing

We orchid lovers draw a lot of happiness from seeing new flower spikes on our favorite orchid plant, or even just seeing an orchid still alive after a brutal Texas summer. This is holds true for me, in any case.

But not everyone requires orchids to be happy. People have many paths toward achieving happiness in this world. Could becoming a dedicated conservationist be a path to happiness? It just might be. Consider this amazing story:

What makes this little country so special?

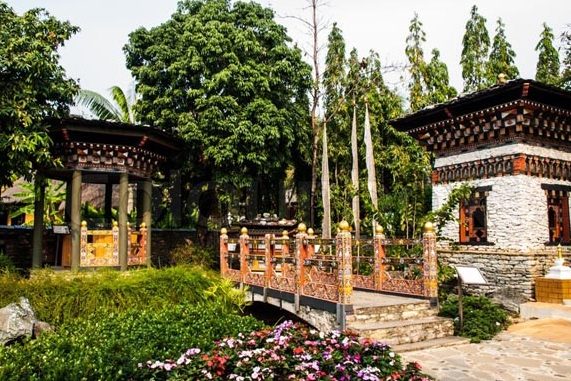

Between China and India sits a small country by name of Bhutan, known mainly for its Buddhist monks and high Himalayan mountains. At one point in its history its name translated to “Land of the Thunder Dragon”, a reference to the dominant Buddhist sect.

Coelogyne nitida

However, this country, which many of us probably know little about, has a lot more going for it than just mountains and monasteries.

Of late Bhutan has become known for its unique “Gross National Happiness” index, established by its government, and intended to nurture a flourishing culture in which prosperity and well-being are tangible, sustainable, and accessible to all. What’s not to like about that?

But wait, it gets even better.

How one small country can be the world leader in goal to be carbon-neutral

Recently, Bhutan has received international acclaim for its commitment to biodiversity. This little country has set for itself the ambitious goal of maintaining at least 60% of its land under forest cover, with 40% retained as national parks, preserves, and protected areas.

The government of Bhutan actively promotes conservation as part of its plan to target Gross National Happiness. They take this commitment so seriously that even their national constitution mentions environmental standards in multiple places.

Bulbophyllum odoratissium

Many positive benefits have ensued, notably that Bhutan’s immense 72% forest coverage is able to absorb 4 million tons of carbon dioxide a year, more than the country’s 2.2 million ton of greenhouse gas emissions, resulting in a net zero greenhouse gas emission rating. How many countries can make such a claim, or even come close? In this excellent TED talk, you can hear more about it.

Bhutan is so committed to biodiversity, they started a special project to protect orchids

Bhutan’s government is totally committed to biodiversity and protecting precious natural resources. So it is no coincidence, and certainly no surprise, that they have also put in place The Thunder Dragon Orchid Conservation Project, administrated by the National Biodiversity Centre (NBC) in Serbithang, a non-departmental organization under the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests. The NBC works in partnership with the Sarasota Orchid Society. Stig Dalström and Ngawang Gyeltshen write about the project in detail in the society’s website.

The aim [of the Thunder Dragon Orchid Conservation Project] is to survey both remote and previously unexplored areas in the country, as well as more easily accessible habitats in order to build a scientific basis for meaningful programs of orchid conservation, cultivation, education, propagation and research. Great efforts are made by the staff at the NBC in collaboration with staff from other governmental departments and international partners, such as the Sarasota Orchid Society, to find ways to utilize orchids as a sustainable economic resource for not only Bhutan, but to serve as a model for other countries as well.

Rhynchostylis retusa

The project extends the documentation work of Pearce and Cribb (Orchids of Bhutan, 2002) as well as that of the late Sithar Dorji (The Field Guide to the Orchids of Bhutan 2008). The Himalayan region is rich is orchid species with 579 species listed. To date 369 of these are recorded from Bhutan, fourteen of them classified as endemic. Continued research and documentation in this rugged area of the world will likely reveal that most of the 579 species actually exist in this remarkable little country.

The Eastern Himalayas have been identified as a global biodiversity hotspot, and counted among the 234 globally outstanding ecoregions of the world in a comprehensive analysis of global biodiversity undertaken by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) between 1995 and 1997. More than 5,400 species of plants are found in Bhutan alone.

To see more photos, as well as learn about remarkable perspectives on the value of conservation, we highly recommend a visit to http://sarasotaorchidsociety.org/orchid-conservation/. After reading further in www.Bhutanfound.org it is easy to understand why there exists a fulfilling connection between the concepts of Gross National Happiness and preserving our environment. Indeed, happiness and quality of life go hand in hand with survival itself. The challenge we face is most elegantly and forcefully defined in Stig Dalström’s Ngawang Gyltshen’s concluding paragraphs:

The authors of this paper [ Dalström and Gyeltshen] would also like to add some observations and facts that often are overlooked in the orchid conservation discussion. It is generally accepted that the orchid family is the largest, most widespread, and most variable plant group in terms of habitat adaptations, pollination syndromes and general morphology.

It is not so well documented, however, that the orchid family quite possibly is the oldest flowering plant group on the planet as well. A private amber collector in the Dominican Republic discovered in 2000 an amber specimen that contained a nowadays extinct bee (Problebeia dominicana), carrying pollinia on its abdomen of a likewise extinct orchid (Meliorchis caribea). The insect was estimated to be approximately 20 million years old. Through elaborate “time clock” computer models, worked out by some scientists, it has since been concluded that the orchid family probably is ca. 100-120 million years old. This came as a total surprise to others who previously had assumed that the orchid family was a rather young and recently developed phenomenon.

In any case, through the multitude of living examples, it is clear that the orchid family represents a very successful complex of organisms with very efficient survival strategies, and we humans can learn a lot from this. Principles, such as living in sustainable populations, utilizing other organisms without destroying and extirpating them, adapting to the environment rather than changing it to suit short term gains, represent sound survival conditions for any living being.

Unfortunately, these simple truths seem to be very difficult for us to acknowledge and accept. Denial is a very powerful human flaw and an excellent way to avoid solving problems. Only by opening our minds and eyes to face reality can we hope to improve the rather dismal environmental condition of our planet. In addition, a much broader understanding of the importance and value of a rich biodiversity, increased respect and empathy for other fellow life forms, and a more level headed approach to how we view our “rights” to limited natural riches, need to be developed in order for the human species, as well as our beloved orchids, to survive on a long term perspective.

As a consequence of the here mentioned (and many other) survival skills, orchids also serve as “canaries in the mine”. When one of the most successful “higher” organisms on the planet no longer can survive, something really bad is happening to the environment. A sad example is the many previously forested areas that have become virtual deserts due to extensive logging and burning practices, usually for short term financial (sometimes survival) gains. The argument that “people have to eat” rings hollow when the long term effects are taken into consideration, and where habitat destruction leads to extermination of living flora and fauna, as well as desertification of former rich and productive habitats.

Basically, and bluntly speaking, almost all (and not limited to) environmental problems in the world today can be summarized by a couple of factors; human greed and over-population!

We all need to be thankful to the country of Bhutan for setting an example for the rest of the world, to the leadership of the Sarasota Orchid society, and to Stig Dalström for his research and art.

Footnote: Stig Dalström is a noted watercolor artist, Curator at the Selby Gardens, and appears in a number of BBC type nature shows. He has his own video series called “Wild Orchid Man”. A trailer of his Ghost Orchid documentary can be viewed below. Trailers of other orchid exploration videos can be found under the “projects” tab in the Sarasota Orchid Society website. As an example of Mr. Dalström’s talent we include here a watercolor depicting the Ghost Orchid from the Florida Everglades. Photos are from the Sarasota Orchid Society website.![]()